The Past.

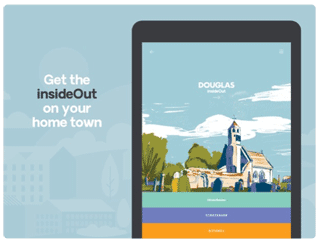

Douglas Lanarkshire

Douglas Lanarkshire

Our Local Community

Our Local Community

Things To See & Do

Things To See & Do

Events & What’s On

Events & What’s On

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

Local Directory

Local Directory

Early days and the Douglas Lineage.

Little is recorded or factually known of the early days of the occupation of the Douglas Valley until Roman times. Even then it is unlikely that their presence was felt particularly deeply in the way that much of the rest of Clydesdale was.

The Douglas family is suggested to have arisen from the native stock of the surrounding area, acquiring name, fame and lands as early as 767 when Donald Bain rebelled against Solvathius, King of Scotland. The ensuing battle saw Bain assured of victory were it not for the arrival of an unknown figure to the King’s aid who, by his prowess, routed the forces of Bain. After the fight the King asked for the man’s identity and was given the reply ‘Sholto dhuglas’, or ‘there, the dark man’. As his reward the King bestowed the honour of a large tract of land in Clydesdale and the surname Douglasse.

In the absence of evidence, it is impossible to know if this is a factual account. The word Douglas itself is more likely to be derived from the Gaelic Dubhglais, black or dark stream, and it is likely that the first feudal landowner took his name from his holding. His original castle was almost unequivocally located on or near its most recent site, with natural protection afforded by the meanders of the Douglas Water. An artificial moat would complete encirclement of the fortress.

Building of a church must have begun shortly after the granting of the Douglas lands with archaeologists deducing that various features suggest no later than 1150. The site is about a mile west of the castle and around it the feudal village could be found, the nucleus of the present village of Douglas. Rebuilt around 1390 by Archibald Douglas (Archibald the Grim), son of The Good Sir James Douglas, it is only the chancel, the ruins of the Inglis Aisle and the clock tower that now remain.

Dedicated to St. Bride, the Patron Saint of the Douglas family, the chancel houses the tombs of some of the medieval Black Earls of Douglas as well as two lead caskets which carry the hearts of The Good Sir James and Archibald ‘Bell the Cat’, 5th Earl of Angus. It boasts some fine 13th Century stained glass and the bell tower contains a working clock reputed to have been gifted by Mary Queen of Scots, dated 1565.

The village’s most famous son is undoubtedly James Douglas, ‘The Good Sir James’, whose efforts were notable in casting off the yoke of England alongside Robert the Bruce throughout the Scottish Wars of Independence.

By the end of the 13th Century the lands of the valley were held by William de Douglas, ‘The Hardy’. Like many of his status, he owned lands in northern England as well as Scotland and as a consequence was due fealty to both Kings. The death of the Maid of Norway in 1290 left Scotland without a sovereign and whilst Hardy and his fellow nobles were initially content to have Edward I of England act as arbitrator, they became increasingly irked and following years of simmering revolt this led to the Scottish Wars of Independence. It wasn’t until Hardi’s death at the tower of London, where he had been held by Edward following the storming of Tranent where Hardi had taken a ward of Edward’s as his bride, that James Douglas, his son, allied himself with Bruce and the other Scottish patriots in an attempt to cast off the yoke of England.

In the Spring of 1307 Douglas Castle was garrisoned by English Soldiers, under a governor appointed by Sir Robert de Clifford. At the time the whole valley was overrun by the hated southrons, but James Douglas knew that he could rely on the loyalty of many of his own men there, and he came secretly into the valley to discover for himself the state of his lands. With the help of his faithful followers, he hatched a plan for retaking the castle and early on the morning of Palm Sunday, when most of the English soldiers were to attend service at the church of St. Bride in the village, Lord James and a few of his adherents came cautiously down the valley and slay the English soldiers as they fled from the church on hearing the cry ‘a Douglas, a Douglas!’. The struggle is said to have been fierce, as the English fought bravely, and there were Scots losses too.

The Castle itself had been left poorly guarded during the service so Douglas had no difficulty in entering. He and his men feasted on the food which had been prepared for the vanquished English, but since it would be impossible to hold the castle against the force which would no doubt be sent against him, Douglas resolved to destroy the seat of his ancestors rather than have it occupied by his enemy. The bodies of men were piled up alongside carcasses of horses, great stores of food and drink, and anything that would burn. The whole mass was fired and James slipped out of the valley as quietly as he had come. The episode has become known as ‘The Douglas Larder’.

It is understood the walls of the castle were left standing and that the fortress was rebuilt by Clifford. John de Thirlwall was made captain of the restored castle, but he too fell a victim to the strategies of James who, whenever he was not fighting alongside Bruce, continued to make sallies into his own district to make his family seat unfit for English occupation.

The legend of James, The Black Douglas, became one of terror and the guardianship of Douglas Castle the least coveted of tasks.

The later exploits of James Douglas have little connection with his own valley, but it should be noted that he was in command of his own division of the Scottish army at Bannockburn, and later Knighted by Bruce on the field of battle after years of service. In 1328 it was Douglas himself who received into his hands from Edward II the agreement by which the independence of Scotland was recognised.

The dying Bruce requested his most loyal friend and trusted lieutenant to carry his heart to the Holy Land in token of his unfulfilled desire to go on crusade, and only a few months later Douglas set out with his embalmed heart within a silver casket. On reaching Spain in August 1330 Sir James joined in battle against the Moors and was mortally wounded rescuing a fellow knight. His body, and the casket, were later recovered and the bones of one of Scotland’s finest warriors laid in his church here in Douglas.

‘Castle Dangerous.’

The only remains of the Castle now are those of a 17th century corner tower, still known as ‘Castle Dangerous’, after the Walter Scott novel which took Douglas Castle as its inspiration. In the 1930’s Charles Douglas-Home, 13th Earl of Home allowed the mining of coal in the park near to the castle, in a philanthropic effort to alleviate local unemployment. The Lanarkshire coal industry, once the mainstay of Scotland’s production, had seen its output almost halved by 1937, with catastrophic consequences for local communities. Because of the mining works the most recent incarnation of the castle was considered to be at risk of subsidence and had to be demolished in 1938.

The Cameronian Regiment.

On 14th May 1689, the Earl of Angus Regiment was raised by James Douglas, Earl of Angus, to assist the fight for religious freedom in Scotland.

Later that year the 1200 strong volunteer regiment, although heavily outnumbered, defeated the Jacobite Army at the Battle of Dunkeld. The regiment became known as The Cameronians in memory of Richard Cameron, a famous and staunch Covenanter.

The statue of the Earl, by Thomas Brock, was unveiled to commemorate the regiment’s bicentenary and depicts the Earl pointing to the site of the field where enrolment of the regiment originally took place. The Earl himself was killed at Steinkirk, Holland in August 1692 whilst battling the forces of Louis 14th of France, at the age of only 21.

The regiment was disbanded in Douglas in 1968 and a commemorative memorial is situated in the Castle policies.

Polish Soldiers.

After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, many Polish soldiers who had escaped from their homeland eventually made their way to Britain.

Many of them were welcomed to Douglas where they settled into village life, making long lasting friendships. Using some of their many talents, the soldiers constructed three monuments as reminders of their time here.

The monuments were situated in different parts of the valley until 2002 when they were restored and brought together, surrounded by a memorial garden.

Industry.

Around 1792 an attempt was made to establish cotton manufacturing in the village but after only a few years it became clear that the financial viability of such an enterprise was questionable.

The factory was located on the Ayr Road, on the Bank Brae between the recently closed Royal Bank and Nursery Avenue. Converted initially to dwellings, they have since been demolished. Whilst cotton manufacture was deemed unsuccessful, it did trigger a period of weaving locally which by 1800 had seen an entire industry grow up, engaging at least half the local population in weaving. Products were sold to the Glasgow markets and the village became so important a centre for weaving at the time that its modest population of 690 grew to over 1300 between 1790 and 1830. The remnants of the gardens of the local weavers can still be traced to the Weavers’ Yards.

Around 1700 it was common for local markets to be held, often on and around the gravestones in the local churchyard. Douglas too had its markets where local buyers and sellers would meet and trade. The poor network of roads at the time meant that anything made locally had to be sold locally and until as recently as 1830 it was common for accounts to be settled and employment sought at such events, or fairs.

Otherwise, it was agricultural tenancies which provided livelihoods and employment locally, and in many cases, this remains. The feudal system of the Valley has remained somewhat unchanged over the centuries though mechanisation has impacted heavily on employment. It was perhaps such mechanisation and the decline of weaving that led to the decision of the 13th Earl of Home to allow the deep mining of the Castle policies for the relief of poverty in the area in the 1930’s. By 1938 undermining of the Castle had caused subsidence to the extent that the same Castle required demolition.

Deep mining of the valley’s rich coal seams continued to provide employment for many at that time and the population of the village was sustained. As the deep mines were closed, subsequently the valley became a focus for opencast coaling.

In the latter part of the 20th century. Douglas welcomed several firms to the area who provided local employment in the form of a plastics factory and several firms who provided components for the oil and gas sector. These companies provided training and skilled work for an eager workforce and while they are now closed, many of those engaged by these firms left the area to continue their careers with them elsewhere. Transport and logistics was a key employer in the area until the early part of the 21st century.

Nowadays, there is no mainstay of local employment. Local jobs are generally in the service or healthcare sectors with most of the population travelling elsewhere for work, generally towards Hamilton and Glasgow.